Introduction: Why Engine Technology Matters

The internal combustion engine revolutionized human civilization by enabling personal mobility, commerce, and industry at an unprecedented scale. For nearly 150 years, gasoline and diesel engines dominated transportation, defining how we live, work, and travel. Today, as environmental concerns and technological breakthroughs reshape the automotive landscape, engine technology stands at a critical crossroads between optimization of traditional combustion systems and the rise of fully electric powertrains.

Understanding engine evolution is essential for any automotive enthusiast, professional mechanic, or conscious consumer. The journey from bulky steam engines to sophisticated turbocharged systems—and now to hybrid and electric motors—reveals how engineering innovation responds to demands for efficiency, performance, and sustainability. This knowledge helps vehicle owners make informed purchasing decisions, maintain their vehicles properly, and appreciate the incredible engineering behind their daily transportation.

Engine technology doesn’t exist in isolation. It intersects with transmission systems, electrical architecture, fuel delivery mechanisms, and emission control systems. The evolution of one influences the development of all others, creating a complex web of technological interdependence that defines automotive progress.

Original Problem: What Did It Solve?

Before the internal combustion engine, human transportation faced fundamental limitations. Steam engines were massive, required lengthy startup periods—sometimes 30 minutes or more—and demanded constant attention to maintain steam pressure. They were impractical for individual vehicle use; they worked for trains and ships, but not for the average person’s daily commute. Early steam-powered carriages were dangerous, unreliable, and could only travel short distances before needing to be stopped for maintenance and fuel gathering.

Horse-drawn carriages remained the primary transportation method through the 1800s, which meant urban roads were choked with congestion, noise, and sanitation problems. Personal mobility was limited to those wealthy enough to own horses and maintain stables. Cities were designed around walking distances and horse transit patterns.

The internal combustion engine solved these fundamental limitations. By burning fuel directly inside a cylinder and harnessing the explosive force to move a piston, engineers created a power source that was compact, reliable, and fast-starting. Unlike steam engines, ICE engines needed no warm-up time. Unlike horses, they didn’t produce waste or require daily feeding. This single innovation transformed society, enabling the development of personal automobiles that eventually democratized transportation and reshaped urban planning.

Historical Timeline: Invention to Present

The path to the modern engine involved decades of experimentation, failures, and incremental improvements. Understanding this timeline reveals how multiple inventors contributed to what we now call automotive progress—it was rarely the work of a single genius, but rather a collaboration spanning continents and generations.

| Year | Milestone | Developer(s) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1769 | Steam-powered vehicle demonstration | Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot | First practical application of mechanical power to wheeled transportation |

| 1807 | First internal combustion engine (Pyréolophore) | Claude & Nicéphore Niépce | Demonstrated ICE concept using controlled dust explosions |

| 1860 | First commercially successful gas engine | Étienne Lenoir | Engine produced in numbers and sold commercially |

| 1876 | Four-stroke engine (Otto Cycle) | Nicolaus Otto | Created the four-stroke principle still used in 99% of cars today |

| 1879 | Reliable two-stroke gas engine | Karl Benz | Foundation for first gasoline-powered automobiles |

| 1892 | Diesel compression-ignition engine | Rudolf Diesel | Higher efficiency, became standard for heavy-duty applications |

| 1905 | Turbocharger patent | Alfred Büchi | Method to increase power without increasing engine size |

| 1925 | Gasoline direct injection (Hesselman engine) | Jonas Hesselman | First direct injection system, improved combustion efficiency |

| 1958 | Wankel rotary engine prototype (KKM) | Felix Wankel, NSU Motorenwerke | Alternative to piston design; smoother operation, compact size |

| 1967 | First commercial rotary engine | Mazda | Cosmo Sport introduced world’s first production rotary vehicle |

| 1996 | Electronic gasoline direct injection (GDI) | Mitsubishi | Precise fuel control revolutionized efficiency and emissions |

| 2000 | Hybrid powertrain mass production begins | Toyota (Prius) | Combined ICE and electric motor technology for consumers |

| 2010s | Turbocharging becomes mainstream | BMW, Audi, Ford, others | Smaller, turbocharged engines meet performance demands with better efficiency |

| 2020+ | Full electrification acceleration | Tesla, Volkswagen, General Motors, others | Battery electric vehicles become viable for mass market |

This timeline shows that major breakthroughs occurred roughly every 20-30 years. The pattern reveals a fascinating reality: innovation accelerates when driven by external pressures. The shift from steam to gasoline happened due to practicality demands. The rise of turbocharging was driven by altitude aviation needs, then performance demands. Today’s electric revolution is being driven by environmental regulations and energy security concerns.

How It Works: Step-by-Step Explanation

The Otto Four-Stroke Cycle (Standard Gasoline Engine)

Understanding the four-stroke cycle is fundamental to understanding 99% of vehicles on the road. This is the principle patented by Nicolaus Otto in 1876, and it remains virtually unchanged today—a testament to elegant engineering.

| Stroke | Process Name | What Happens | Piston Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Intake (Induction) | Intake valve opens; air-fuel mixture is drawn into the cylinder as the piston moves down. The cylinder fill with combustible charge. | Down |

| 2nd | Compression | Both intake and exhaust valves close; piston moves up, compressing the air-fuel mixture. Compression ratio typically 9:1 to 14:1 in modern engines. | Up |

| 3rd | Power (Combustion) | Spark plug ignites the compressed mixture, creating an explosion that forces the piston down with tremendous force. This is where energy is extracted from fuel. | Down |

| 4th | Exhaust | Exhaust valve opens; piston moves up, pushing burned gases out of the cylinder. Cylinder is now ready for the next intake stroke. | Up |

This four-stroke cycle repeats thousands of times per minute in a running engine. In a typical car engine with 6,000 RPM idle speed, each cylinder is executing this complete cycle 50 times per second. In a four-cylinder engine, that’s 200 combustion events per second. The coordination of this across multiple cylinders, each timed to fire in precise sequence, is managed by the engine’s crankshaft and valve timing system.

Diesel Compression-Ignition Process

Rudolf Diesel’s 1892 innovation changed combustion fundamentally. Instead of using a spark plug to ignite fuel, diesel engines rely on the heat generated by compression alone. When air is compressed to a compression ratio of 16:1 or higher, it becomes hot enough to spontaneously ignite diesel fuel injected into the cylinder. This requires stronger engine construction but delivers greater efficiency—typically 30-40% better fuel economy than equivalent gasoline engines.

Turbocharged Engine Operation

A turbocharger uses exhaust gas energy that would otherwise be wasted. Hot exhaust gases spin a turbine wheel (turbine side), which is connected by a shaft to a compressor wheel (compressor side). The spinning compressor wheel sucks in and compresses incoming air, forcing more oxygen into the combustion chamber. More air means more fuel can be burned, producing more power from a smaller engine. Modern turbochargers can increase engine output by 30-50%.

Direct Injection System

Traditional fuel injection (port injection) sprays fuel into the intake manifold, where it mixes with air before entering the cylinder. Direct injection skips this step and sprays fuel directly into the combustion chamber under high pressure. This allows more precise control over the air-fuel mixture, better combustion efficiency, and faster cold starts. Electronic control systems can vary injection timing and pressure in milliseconds, optimizing for current driving conditions.

Hybrid System Architecture

A hybrid vehicle uses both an internal combustion engine and an electric motor, each providing power to the wheels depending on driving conditions. During low-speed acceleration, the electric motor handles power delivery while the ICE remains off, saving fuel. The electric motor is powered by a rechargeable battery that gets charged through regenerative braking—capturing energy normally lost during braking and converting it back to electricity.

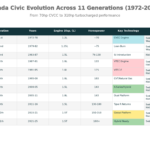

Evolution Through Generations: Improvements Over Time

Generation 1: Early Carbureted Engines (1876-1980)

From Nicolaus Otto’s first four-stroke engine through the 1980s, gasoline engines used carburetors to mix fuel and air. A carburetor is a mechanical device that uses a suction created by incoming air to draw fuel through calibrated jets, mixing them in the correct ratio. This simple system was inexpensive to manufacture but crude in its precision. Cold starts were difficult, efficiency was poor (typically 8-12 MPG), and driveability was compromised in cold weather when fuel was sluggish to atomize.

These early engines were naturally aspirated—they relied only on atmospheric pressure to fill the cylinders with air. Displacement (engine size measured in liters or cubic inches) was the primary way to increase power. A 1970s muscle car might have a 455 cubic-inch (7.5L) engine producing just 375 horsepower, while a modern 2.0L turbocharged engine produces comparable or greater power.

Generation 2: Electronic Fuel Injection Era (1980-2000)

The shift to electronic fuel injection (EFI) in the 1980s represented a revolutionary step forward. A computer (engine control unit or ECU) now managed fuel delivery by controlling solenoid injectors that spray precise amounts of fuel into either the intake manifold or directly into cylinders. This allowed engines to adapt fuel mixture in real-time based on dozens of sensors monitoring temperature, oxygen content, air mass flow, throttle position, and more.

This era brought dramatic improvements in cold weather starting, emissions control, and fuel efficiency. A 1990 car with electronic fuel injection could achieve 20-25 MPG where a comparable 1970 carbureted car managed only 8-10 MPG. The addition of three-way catalytic converters and oxygen sensors meant that engines could precisely maintain a stoichiometric air-fuel ratio (14.7:1 for gasoline), optimizing both combustion and emissions reduction simultaneously.

Generation 3: Turbocharged Downsizing (2000-2015)

As emissions regulations tightened globally, automakers faced a dilemma: consumers wanted performance and practicality, but regulations demanded lower CO2 emissions. The answer was turbocharging combined with smaller displacement engines—a concept called “downsizing.”

Rather than a 3.5L naturally aspirated engine, manufacturers could install a 2.0L turbocharged engine that produced equivalent power but consumed 20-30% less fuel in real-world driving. The turbocharger also helped diesel engines become cleaner, eventually making modern diesels viable in passenger cars despite emissions challenges. Variable valve timing, continuously adjustable cam profiles, and increasingly sophisticated engine management computers enabled precise optimization for different driving conditions.

This generation saw the explosion of turbocharged four-cylinder engines in performance vehicles. What was once considered underpowered became the platform for accessible performance cars. A turbocharged 2.0L could deliver 300+ horsepower, matching naturally aspirated V6s of previous generations while using significantly less fuel.

Generation 4: Direct Injection Optimization (2010-2020)

Gasoline direct injection matured in this generation, becoming industry standard rather than premium feature. The combination of direct injection with advanced turbocharging and variable valve timing created remarkably efficient engines. Combustion efficiency improved, allowing higher compression ratios and increased power density.

This era also saw widespread adoption of cylinder deactivation technology—disabling half a V8’s cylinders during light-load highway driving—and hybrid powertrains transitioning from novelty to mainstream. A turbocharged direct-injection engine with cylinder deactivation could achieve 35+ MPG on the highway while delivering strong acceleration, a combination that seemed impossible just a decade prior.

Generation 5: Hybrid Integration & Electrification Begins (2015-Present)

Today’s engines rarely operate alone. Hybrid systems became mainstream—not just for economy cars but for performance vehicles (Porsche Panamera Hybrid, BMW M440i xDrive). Mild hybrid systems with 48-volt electrical architecture become increasingly common, allowing engines to shut off during braking and coasting while providing electric boost during acceleration.

Simultaneously, battery electric vehicles are becoming viable for mainstream consumers as battery costs decline and charging infrastructure expands. However, the internal combustion engine isn’t disappearing—it’s evolving. Modern ICE engines are cleaner, more efficient, and more sophisticated than ever, but they’re increasingly integrated with electric power rather than standing alone.

Current Technology: Modern Implementation

Advanced Gasoline Direct Injection Systems

Today’s GDI systems inject fuel at pressures up to 300 bar (4,350 PSI), atomizing fuel into incredibly fine mist for optimal combustion. Piezoelectric injectors can open and close in fractions of a millisecond, allowing multiple injection events per combustion cycle. The first injection cools the chamber, the second ignites—this sophisticated control enables engines to run lean (more air, less fuel) during part-load conditions, dramatically improving efficiency.

Twin-Turbo and Variable Geometry Systems

Modern turbocharged engines often use two turbochargers—one small unit for quick spool-up at low RPMs, one larger unit for sustained power at high RPMs. Variable geometry turbos adjust turbine blade angles in real-time, optimizing boost pressure across the entire RPM range. Some premium engines employ sequential turbocharging, where each turbo activates at different RPM bands.

Engine Management & Real-Time Optimization

Modern engine control units process data from over 100 sensors hundreds of times per second. Fuel injection timing is adjusted for ambient temperature, barometric pressure, fuel octane rating (via knock sensors), intake air temperature, coolant temperature, and exhaust oxygen content. Ignition timing, valve timing, and turbo boost pressure are all dynamically optimized. Some luxury vehicles use machine learning algorithms that adapt to individual driving patterns.

Efficiency Technologies

Cylinder deactivation: A V8 automatically disables 4 cylinders during highway cruising, operating as a V4. Some advanced systems can deactivate cylinders on demand, even during acceleration. This can improve highway MPG by 10-15%.

Variable valve timing (VVT): Adjusting when intake and exhaust valves open and close optimizes power delivery, efficiency, and emissions. Advanced dual VVT systems adjust both intake and exhaust cams continuously.

EGR systems: Exhaust gas recirculation routes some exhaust back into the intake, cooling combustion and reducing nitrogen oxide emissions.

Lightweight construction: Modern engines use aluminum blocks and heads, titanium valves, and carbon fiber components to reduce weight, improving both performance and efficiency.

Emission Control

Modern engines meet Euro 6 and EPA Tier 3 standards through sophisticated systems. Selective catalytic reduction (SCR) technology in diesels uses urea injection to break down harmful nitrogen oxides. Gasoline engines use three-way catalytic converters. Particulate filters capture soot particles. These systems are so effective that modern cars can exceed current air quality in cities by drawing in polluted air and exhausting cleaner air.

Advantages vs. Disadvantages: Trade-offs

| Engine Type | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Naturally Aspirated Gasoline | Simple mechanics, proven reliability, linear power delivery, wide fuel availability, low maintenance costs | Lower efficiency (20-25 MPG), higher emissions, smaller power output per displacement, longer warm-up time |

| Turbocharged Gasoline | High power density (300+ HP from 2.0L), better fuel economy with performance, faster acceleration, good for smaller vehicles | Turbo lag in older systems, higher combustion temperatures requiring premium fuel, added complexity, potential turbo failure expense |

| Diesel | 30-40% better fuel economy than gasoline, higher torque, lower fuel cost (typically), proven longevity (engines run 300k+ miles commonly) | Higher emissions of NOx and particulates, more expensive initial purchase, diesel fuel less available in some regions, louder operation, slower acceleration |

| Rotary | Compact size, very smooth operation, high RPM capability, excellent power-to-size ratio, unique character and sound | Poor fuel economy, difficulty meeting emissions standards, apex seal wear, limited manufacturers (primarily Mazda now) |

| Hybrid (ICE + Electric) | Excellent city fuel economy (30-50 MPG), regenerative braking captures lost energy, lower emissions, no plug-in required (non-PHEV) | Higher purchase price, more complex systems, added weight from battery, smaller cargo space, delayed throttle response (traditional hybrids), expensive battery replacement |

| Battery Electric (EV) | Minimal emissions (depending on electricity grid), lowest operating cost per mile, instant torque, quiet operation, improved air quality in cities | Range limitations (200-300 miles typical), long charging time, high initial cost, battery degrades over time, limited infrastructure in rural areas, cold weather efficiency loss |

The Modern Efficiency Paradox

Despite 150 years of development, the thermal efficiency of internal combustion engines has plateaued around 35-40% for gasoline and 45-50% for diesel. This means that 60-65% of fuel energy is still wasted as heat through the exhaust and cooling systems. Electric motors, by contrast, achieve 85-90% efficiency in converting electrical energy to mechanical work. This fundamental advantage of electrification cannot be overcome by further optimization of combustion engines.

However, battery manufacturing, electricity generation, and grid infrastructure must also be considered when evaluating true environmental impact. A battery electric vehicle charged from a coal-heavy electricity grid may be only marginally cleaner than a hybrid. But in regions with renewable energy, EVs are dramatically cleaner.

Real-World Examples: Cars Using This Technology

Naturally Aspirated Icons

Porsche 911 Carrera (Air-cooled, 1963-1998): The original air-cooled flat-six established a legend with simple naturally aspirated engineering. Modern variants have abandoned naturally aspirated engines, showing how performance expectations have evolved.

Honda Civic Si: The Civic Si carries forward the naturally aspirated tradition, proving that high-revving, naturally aspirated engines still have enthusiast appeal despite efficiency disadvantages.

Turbocharged Performance Leaders

BMW 335i/M440i (N54/B58 Twin-Turbo): The N54 was revolutionary—a 3.0L turbocharged six-cylinder producing 335 horsepower, matching V8 performance while improving fuel economy. The newer B58 continues this philosophy with even greater refinement and reliability.

Ford Ecoboost Engines: Applied turbocharged downsizing to mainstream vehicles. A 2.0L EcoBoost delivers V6-like performance and towing capacity in a compact package.

Audi RS3 & RS4 (2.5L Turbo 5-Cylinder): High-revving five-cylinder turbo engines pushing 400+ horsepower prove that smaller displacement doesn’t mean less character or performance.

Direct Injection Excellence

Mercedes-AMG A45 (2.0L Turbo DI): Produces 381 horsepower from 2.0 liters—a power density that seemed impossible a decade ago, achieved through direct injection optimization and sophisticated turbocharging.

Volkswagen Golf GTI (2.0L TSI): The modern GTI demonstrates how direct injection with supercharging and turbocharging creates efficient performance in an accessible package.

Rotary Engine Heritage

Mazda RX-7 (1978-2002): The spiritual successor to the Cosmo, the RX-7 became the platform for rotary engine development. Its rotary engines never dominated the market but achieved cult status among enthusiasts for their unique character and high-RPM capability.

Mazda RX-8 (2003-2012): The last mass-produced rotary, equipped a more practical four-door sports car. Though discontinued, rotary engines remain the ultimate niche engine with devoted followers.

Diesel Excellence

BMW 330d (B47 Twin-Turbo Diesel): Produces 260 horsepower and exceptional torque while achieving 45+ MPG highway. Shows how modern diesels combine performance with efficiency.

Porsche Cayenne Diesel (V8 TDI): Demonstrates that diesel technology can power performance vehicles, not just economy cars.

Hybrid Game-Changers

Toyota Prius (1997-present): Established hybrid viability for mass market. Early models achieved 50+ MPG combined, saving owners significant fuel costs and inspiring development of hybrid versions across manufacturers.

Porsche 918 Spyder (Hybrid Hypercar): Combined V8 and hybrid electric power to achieve supercar performance with better fuel economy than non-hybrid rivals, proving hybrids aren’t just for economy cars.

BMW M440i xDrive (Turbocharged + 48V Mild Hybrid): Modern intermediate solution—a turbocharged six-cylinder with integrated electric motor assistance provides performance with reasonable efficiency, representing current mainstream luxury approach.

Electric Future

Tesla Model S Long Range (Dual Motor Electric): 405 miles of EPA range and sub-4-second 0-60 acceleration prove electric powertrains can deliver performance and practicality simultaneously.

Porsche Taycan Turbo (800V Electric): An all-electric sports car that accelerates as quickly as the gas-powered 911 Turbo, proving that EV performance can rival traditional engines in real-world acceleration.

Maintenance & Operation: Practical Owner Information

Oil Change Intervals & Synthetic Oil

Modern turbocharged direct-injection engines operate at higher temperatures and pressures, requiring premium synthetic oil to maintain protective film on engine surfaces. Many manufacturers now recommend 10,000-mile intervals with synthetic oil, compared to 3,000-5,000 miles with conventional oil in older engines. Some luxury brands extend intervals to 15,000 miles. Always follow your vehicle’s maintenance schedule—turbocharged engines are more sensitive to oil viscosity and change intervals than naturally aspirated engines.

Fuel Quality Matters More Than Ever

Direct injection engines are sensitive to fuel quality. Low-quality fuel can cause carbon deposits to accumulate on intake valves, reducing performance and efficiency. Premium gasoline (91-93 octane) is recommended for turbocharged engines not only for performance but also for reliability. Some high-performance vehicles require premium fuel due to high compression ratios. Using regular fuel in an engine designed for premium can cause detonation (engine knock), potentially causing serious damage over time.

Turbocharger Maintenance

Turbos are incredibly durable when properly maintained. The key factors are allowing adequate warm-up time before driving aggressively after a cold start, avoiding sudden shutdowns after high-boost driving (turbochargers need 30-60 seconds at idle to cool), and using quality oil. Turbo failures are rare in modern cars but can be expensive ($1,200-$3,000 replacement). However, most original turbos last the lifetime of the vehicle with proper care.

Hybrid-Specific Considerations

Hybrid systems require no special maintenance beyond regular oil changes and fluid service. The battery pack is carefully managed by onboard computers and very rarely requires replacement before the vehicle reaches 150,000+ miles. When batteries do fail, replacement costs $2,500-$8,000 depending on the vehicle, though this often occurs well after the warranty period expires. Regenerative braking systems mean brake pads last significantly longer in hybrids compared to conventional cars.

Diesel Engine Ownership

Diesel engines are legendary for longevity—300,000+ mile engines are common in both personal vehicles and commercial trucks. They require minimal maintenance beyond regular oil changes and occasional fuel filter changes. Diesel fuel includes oil that naturally lubricates the fuel pump and injectors, so fuel quality is less critical than with gasoline. However, modern diesels have complex aftertreatment systems (SCR, DPF) that require specific fuel and fluid types. European diesels require AdBlue (urea solution) refills approximately every 10,000 miles.

Knowing Your Engine’s Limits

Turbocharged engines produce maximum boost pressure only at higher RPMs or under load. During normal city driving, a 2.0L turbo operates much like a naturally aspirated engine. Aggressive driving habits increase fuel consumption and component wear. Allowing adequate warm-up time (just 15-30 seconds in modern systems) before driving hard is essential for engine longevity. Cold-starting a turbo directly into aggressive driving can cause turbo bearing wear and increased engine wear.

Future Direction: Where Engine Technology Is Heading

Electrification is Inevitable

Every major automaker has committed to electrification targets. Porsche plans to eliminate gasoline engines by 2030. Mercedes-Benz targets all-electric lineup by 2030. BMW will offer electric versions of all models by 2025. Volkswagen Group aims for 70% electric vehicles by 2030. This isn’t aspirational marketing—billions of dollars of investment and manufacturing capacity are being redirected toward electric vehicles.

However, “electrification” doesn’t necessarily mean elimination of internal combustion engines. More likely, hybrids and plug-in hybrids become intermediate solutions while battery costs decline and charging infrastructure expands. A plug-in hybrid offers 40-60 miles of electric-only range for daily commutes, with a gas engine as backup for longer drives.

Efficiency Improvements in Combustion Engines

Despite electrification’s rise, combustion engine research continues. Advanced variable compression ratio technology allows engines to automatically adjust compression ratios depending on driving conditions—high compression for efficiency during cruising, lower compression for knock resistance during high boost. Some prototypes achieve 45%+ thermal efficiency. Homogeneous charge compression ignition (HCCI) engines combine features of gasoline and diesel engines, potentially improving efficiency by 20%. However, whether these reach production before electric powertrains become dominant remains uncertain.

Hybrid Technology Evolution

Mild hybrid systems with integrated electric motors become increasingly common. Porsche’s new 911 uses 48-volt architecture to provide electric boost and implement cylinder deactivation more effectively. Larger plug-in hybrids with 100+ mile electric range appeal to buyers who want ICE range backup but can satisfy 90% of driving through electricity. These represent a realistic bridge toward full electrification.

Synthetic & Alternative Fuels

Some manufacturers explore synthetic fuels (e-fuels) produced using renewable electricity and captured carbon dioxide. These could theoretically allow existing gasoline and diesel vehicles to operate with net-zero lifecycle emissions. However, the energy loss in creating synthetic fuel (converting electricity to liquid hydrocarbons) makes this less efficient than direct battery electric power. Synthetic fuels likely serve niche applications (aviation, marine) rather than mainstream vehicles.

Battery Technology Advances

Current lithium-ion batteries are approaching their theoretical efficiency limits. Solid-state batteries promised for the late 2020s could increase energy density by 50-100%, enabling electric vehicles with 400-500 mile range and faster charging. Sodium-ion batteries may offer lower costs and improved thermal stability. Solid-state technology could finally make electric vehicles cost-competitive with gasoline on purchase price, accelerating electrification dramatically.

Infrastructure Development

Rapid charging networks are expanding globally. Tesla’s Supercharger network now exceeds 50,000 global locations. Government incentives drive charging infrastructure investment in Europe and Asia. Within 5-10 years, roadside charging should be as ubiquitous as gasoline stations in developed nations. This infrastructure development may be the single biggest factor enabling mass electric adoption.

The Last Gasoline Engine

Your internal combustion engine is likely a bridge technology. If you purchase a vehicle today, it may be one of the last gasoline-powered cars produced. Future classic car collectors may view modern turbocharged engines the way we now look at carbureted V8s—impressive for their time, but fundamentally limited compared to what followed. The internal combustion engine’s 150-year reign is entering its final decades, making this an extraordinary time to understand and appreciate these remarkable machines.

Legacy and Importance of Engine Evolution

The internal combustion engine represents one of humanity’s greatest engineering achievements. For 150 years, continuous innovation—from Nicolaus Otto’s four-stroke principle through modern direct injection and turbocharging—has taken the fundamental concept of burning fuel inside a cylinder and refined it into remarkably efficient, clean, and powerful machines. Each generation of engineers solved problems that their predecessors thought impossible, pushing toward theoretical limits while staying within practical and economic constraints.

Understanding engine evolution provides perspective on how technology develops. Breakthroughs rarely occur overnight; they typically emerge from decades of incremental improvements, failed experiments, and occasional inspired leaps. The shift from steam to internal combustion took 30 years of competition. Turbocharging took 40 years from patent to widespread automotive use. Electronic fuel injection took 20 years from laboratory concept to mass production.

Today’s engine technology represents the peak of internal combustion optimization. Modern turbocharged direct-injection engines are marvels of engineering—some producing over 400 horsepower per liter of displacement while meeting stringent emissions standards and achieving fuel economy that seemed impossible just a decade ago. Yet this peak arrives as electrification fundamentally changes automotive power. The fact that engineers are still pushing gasoline and diesel engines to new limits, even as the industry pivots toward electric propulsion, speaks to both the fundamental elegance of combustion engines and their inevitable role as a bridge technology.

For vehicle owners, this knowledge matters. Understanding how your engine works, how its systems interact, and what maintenance it requires enables better decision-making around vehicle selection, operation, and repair. For enthusiasts, appreciating engine evolution contextualizes why certain vehicles are significant—why a turbocharged Porsche 911 represents a different philosophy than a naturally aspirated one, why a Mazda RX-7 with rotary engine has cult status, why modern diesel technology appears in luxury vehicles.

Whether you’re considering an ICE vehicle purchase, operating an existing engine, or simply curious about automotive technology, remember that the engine under the hood is the product of 150 years of human ingenuity. It’s a remarkable machine, and understanding its journey from steam-powered experiments to sophisticated electronic systems enriches the appreciation of every drive.